Essay by Clara Jeanroy, Nature For Health Youth Ambassador and at the time of writing the essay Wageningen University & Research Master Student Forest and Nature Conservation (now Clara is graduated)

Introduction

The place we give to nature in our living space has changed greatly over the course of our civilisation. Indeed, during the Middle Age and in order to protect population from diseases, European medieval cities were built fully separated from nature. However, during the 17th century, the art of garden design flourished, notably in the aristocracy, leading to the firsts “garden cities”. Urban nature evolved again in the 19th century with the hygienist movement, considering nature as a necessary benefit for people, with the first urban parks created, based on social, economic, health and aesthetic objectives (1). Nowadays, urbanisation is characterized by strong levels of population density, leading to many infrastructures (roads, buildings…) and strong competition in land use. Urban environments are therefore primarily artificial, and their level of biodiversity differs greatly from one city to another. In 2018, the UN World Urbanisation Prospects estimated that 55% of the world’s population (4 billion) lived in urban areas, and this proportion is expected to increase to 68% (7 billion) by 2050. Therefore, more and more people, including part of the world’s elite, the current and in-becoming decision-makers, will live and be raised in environments strongly separated from “wild” nature.

As urban space is expected to grow, its contribution to solving the current biodiversity crisis and reaching the global aim of sustainability needs to be addressed. Especially its role for conservation and the education of new generations towards nature.

This essay will thus aim at understanding some benefits of implementing biodiversity in cities. We will look at the way urban biodiversity can benefit nature conservation and humans, taking the prism of children development. Finally, as these relationships are dynamic, we will look

at the potential long-term effects of children development on nature and sustainability, as well as potential limits of urban biodiversity.

1 | Urban spaces and nature

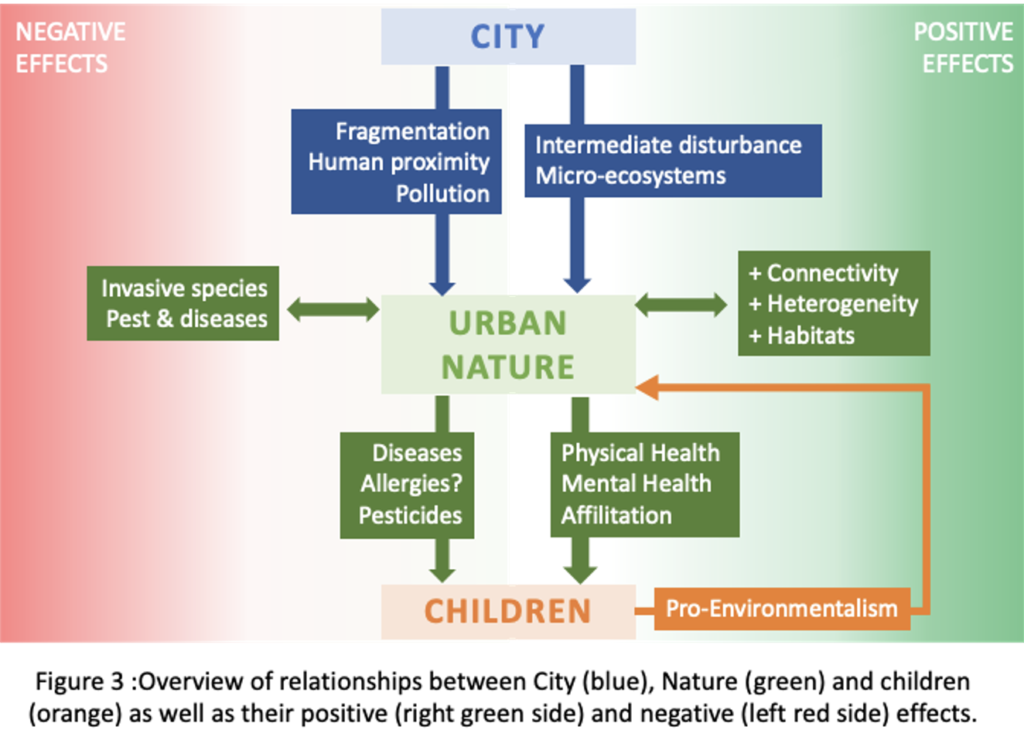

1.1 Threats for nature in urban centres

Urban centres inevitably pose threats to biodiversity; As a matter of fact, urbanisation was shown to be a major cause of decrease in species richness (2) as well as native species extinction (3), contributing to species homogenization across cities worldwide. Indeed, Wittig and Becker (2010) found that 80% of the flora found in Baltimore was also present in most European cities (4).

Such a lack of diversity can be explained by the strong habitat fragmentation caused by infrastructures (buildings, roads). As a matter of fact, fragmentation can for instance limit seed dispersal and increase mortality rates of big urban carnivores, often killed on roads (5).

Urban pollution also has harmful effects on biodiversity: Chemicals such as pesticides affect development, cognitive abilities, physiology & behaviours in many animals (6). Moreover, noise and light pollution also impact behaviours and health such as modifying birds’ singing pitch (8)

or altering the expression of circadian clock genes in many taxa (controlled by succession of daylight and night’s darkness) (7). Therefore, these characteristics alongside others such as human proximity, altered climate or bad soil quality make it hard for both vegetation and animals to strive in urban contexts.

1.2 Urban spaces, an opportunity for biodiversity

Despite the different threats previously mentioned, cities can represent a great opportunity for biodiversity conservation. Firstly, the negative impact on nature varies significantly depending on the level of urbanization. Moderate levels encountered in suburban areas can even lead to increase in species richness (3). This effect may be due to the “intermediate disturbance hypothesis” where moderate levels of human disturbance promote habitat heterogeneity along with the coexistence of native and introduced species in micro-ecosystems (for example urban private gardens: ponds, nest-boxes, compost heaps, trees…) (9). This positive effect of urban habitats can be significant if surrounded by intensively used and impoverished landscapes. Secondly, urbanisation does not automatically result in species extinction and some endangered taxa have been known to establish self-sustaining urban populations (10).

Moreover, implementing more urban natural spaces can help create ecological corridors and connectivity, allowing migration and limiting small-sized populations, more sensitive to extinction. Therefore, nature in cities, can be a successful strategy in improving conservation but strongly depends on the intensity of urban land use, habitat continuity, species ability to adapt to human proximity and management practices.

2 | Nature for the new generation

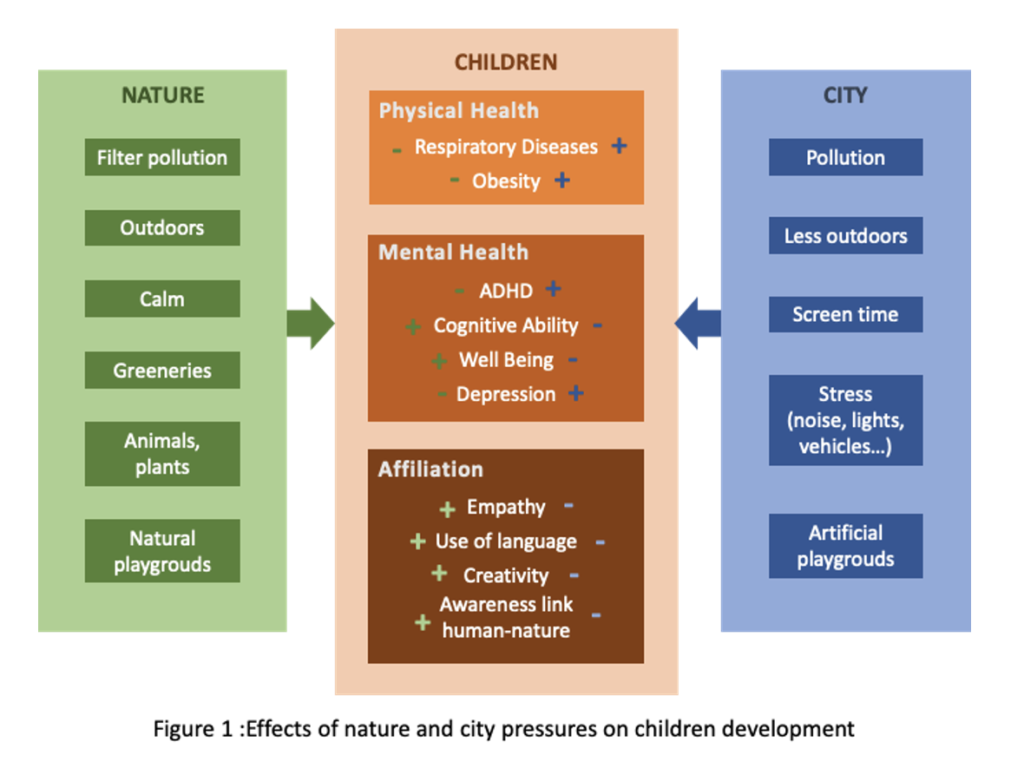

2.1 Nature mitigates cities’ pressures on children

Cities cannot only impact negatively biodiversity but can also be harmful to human’s health and well-being. In fact, adults in heavily built up neighbourhoods with low access to nature have in average worse mental and physical health, as well as are less engaged socially (11). However, an even more pressing issue is understanding how this stressful environment affects children and their development.

In terms of physical health, urban air pollution has been shown to increase asthma and respiratory issues (12) while urban vegetation can improve air quality by removing air pollutants (13).

In addition, there is a positive association between green spaces access, outdoor play & physical activity in children. Epstein et al. (2012) even found that children under medical treatment for obesity had greater decrease of body mass index if they had access to more parkland (14).

Nature not only improves physical health but also concentration and memory ability. Children diagnosed with ADHD demonstrate similar levels of concentration after a walk in the park than after taking their medicine (15). Moreover, a study showed that third-grade students in Massachusetts ranked higher on standardized tests of English and mathematics when

there were more greeneries around their schools (16).

Lastly, nature was shown to better psychological well-being. In Scotland, children living less than twenty minutes from a green space had better mental health, regardless of family income (17). More generally, proximity with green space predicts higher well-being in children, leading to lower rate of depression and greater sense of self-worth. It also predicts stronger emotional adjustment: the more stressful the event experienced by children, the more strongly nature acts as a buffer (12). By improving in such manner well-being, urban nature contributes to ameliorate urban lifestyles and quality of life, both for children and adults.

2.2 Connection with the natural world (human and non-human)

Nature also strongly shapes the way children interact with their surroundings and their level of affiliation. Nussbaum (2011) described this concept as such: “being able to live with and towards other people, engage in various forms of social interaction, imagine situation

of another, show concern for others” (12). Interactions between children during games are good examples of how natural spaces lead to stronger affiliation than urban spaces. Indeed, while in artificial playgrounds children tend to display hierarchy based on physical prowess, natural play areas involve more fantasy and a hierarchy between children based on the use of language and creativity (12). Therefore, natural playgrounds promote children to become strong elements of social groups by stimulating more inventiveness and self-expression.

On another note, nature also leads children to being more empathetic and concerned for other life forms as well as raises stronger awareness of human and nature interdependence (18). However, children raised in urban areas, can find nature uncomfortable, disgusting and even scary because of the poor frequency and quality of their experiences with biodiversity. Thought, positive effects of affiliation can be reinforced in children after short periods of time in nature such as through five-day environmental education programs (19).

3 | A long term approach to conservation

3.1 Psychology: human and nature connection as a leverage

Another issue concerning urban children, is that their most regular “contact” with biodiversity consists of nature witnessed through screens. If “virtual” nature can be a good opportunity to spark interest for the natural word, it can be biased and does not reproduce the benefits of spending real time in it. R. C. Moore even stated, “Children who live exclusively in a secondary media environment inevitably pose a threat to the future of the planet because such images substitute vague dreams for those intuitive values that can only be acquired by life experience of the biosphere’’ (20). He therefore implies that lack of nature experience can be in some way harmful to the environment. Indeed, it was shown that environmental behaviours of urban children were predicted by the frequency of their contacts with nature (20). Furthermore, Liefländer (2013) found that adult pro-environmentalism is positively related to childhood experiences in nature (21). Hence, increasing children’s connection with the natural world could help promote more sustainable attitudes in later life (22).

3.2 Positive feedback: education & infrastructures

Bringing children and nature together is therefore a crucial aspect to consider for pro-environmentalism in the next generations. In that regard, education plays a big role in building children’s connection with the environment. Adult figures that communicate nature’s value can be a powerful tool to increase pro-environmentalism and educational programmes can enhance affiliation significantly. Consequently, more urban nature can promote more educational activities. Theses can in turn lead to increased connectedness of children (and mostly pre-teens) with nature (21).

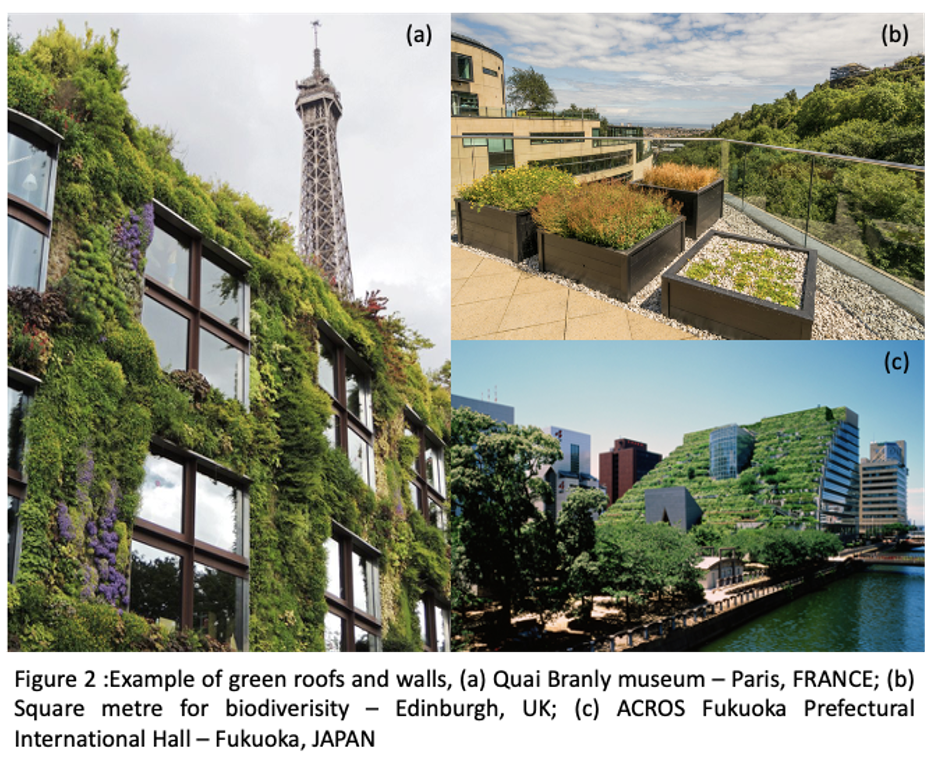

These social and educational requirements for nature (health, well-being…) can therefore promote the inclusion of more urban nature through adaptative architecture (green roofs, parks, green walls, water areas…). Which can then support and protect biodiversity. For example, the “square metre for biodiversity” initiative in Edinburgh, promotes butterfly connectivity and richness by vegetating urban roofs in the city (b).

4 | Limits

4.1 Limits of nature in cities

Integrating more biodiversity in the city can however lead to undesired outcomes even for biodiversity itself. Indeed, cities create ideal conditions for opportunistic and generalist species. Species such as the rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameria) tend to become invasive, hence generating threats to local biodiversity. A good example is the house crow Corvus splendens, already present in most developed cities worldwide and expected to colonise new areas in Central America, equatorial and West Africa, the Caribbean and Southeast Asia (23). These pest and invasive species can remove habitats for native species, thus leading to a decrease in the local fauna and flora (3).

Wildlife attracted by city opportunities can also create nuisance for humans with for example big urban carnivores (coyotes, foxes…) feeding on domestic animals and anthropogenic waste (8). Other risks and disturbances can be very diverse such as diseases spreading from wildlife

to domesticated species, risks of large trees falling down and minor inconveniences such as birds opening milk bottles, a phenomenon that occurred in the UK during the 20th century (24).

4.2 Limits of nature for people

Just as with biodiversity, urban nature can put pressures on humans. Illnesses such as Lyme disease can represent threats to human health in the Netherlands and the rest of Europe notably. Furthermore, not all vegetation is efficient at filtering air and some even lead to air pollution accumulation (25). Moreover, their influence on respiratory diseases is unclear: despite their filtering properties, they release pollen which can cause allergies (12). Nonetheless, the “diversity hypothesis” stipulates that leaving near greater biodiversity helps increase skin bacteria’s diversity and decrease allergy sensibilization. Good management and treatment

of urban vegetation is therefore crucial, mostly since pesticides use leads to adverse health effects and can contribute to various issues including miscarriages, respiratory and lung diseases, learning disabilities etc. (12). Naturally, these are very complex and multifactorial interactions with sometimes non-conclusive nor significant effects of nature on health on large scales.

Lastly, as previously mentioned, not all children have positive feelings toward nature, mainly due to parent’s values as well as their sociocultural background (19). On that note, it should be important to consider which type of daily nature exposure children are facing when implementing more urban biodiversity. Nonetheless, research seems to find that negative relationship to nature does not eliminate positive effect its frequent contact provides (19).

Conclusion

To conclude, implementing biodiversity in cities enables allocating more space to enhance nature conservation. It can also greatly improve the lifestyle and development of both children and urban dwellers, consequently reinforcing the concept of socio-ecological systems. The multiple other benefits of urban nature caused by ecosystem services are vast and can contribute to making cities more resilient to climate change.

Further studies should though be addressed to better understand the multifactorial relationship between nature and children both in term of health and psychology. Finally, the precise functions of urban habitats and their importance for biodiversity at a large scale requires deeper understanding in order to ensure the most efficient nature management.

As most future stakeholders are growing up in cities, reinforcing their link to the natural environment during their childhood can enhance their future will to protect and conserve. Therefore, positively impacting children development through nature implementation can lead to new generations deeply connected and concerned by the future of the planet.

REFERENCES

(1) Arnould, P., Le Lay, Y., Dodane, C. and Méliani, I., 2011. La nature en ville : l’improbable biodiversité. Géographie, économie, société, 13(1), pp.45-68.

(2) McKinney, M., 2008. Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosystems, 11(2), pp.161-176.

(3) Czech, B., Krausman, P. And Devers, P., 2000. Economic Associations among Causes of Species Endangerment in the United States. BioScience, 50(7), p.593.

(4) Wittig, R. and Becker, U., 2010. The spontaneous flora around street trees in cities—A striking example for the worldwide homogenization of the flora of urban habitats. Flora – Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 205(10), pp.704-709.

(5) Bateman, P. and Fleming, P., 2012. Big city life: carnivores in urban environments. Journal of Zoology, 287(1), pp.1-23.

(6) Zala, S. and Penn, D., 2004. Abnormal behaviours induced by chemical pollution: a review of the evidence and new challenges. Animal Behaviour, 68(4), pp.649-664.

(7) Gaston, K., Duffy, J., Gaston, S., Bennie, J. and Davies, T., 2014. Human alteration of natural light cycles: causes and ecological consequences. Oecologia, 176(4), pp.917-931.

(8) Mockford, E. and Marshall, R., 2009. Effects of urban noise on song and response behaviour in great tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276(1669), pp.2979-2985.

(9) Gaston, K., Warren, P., Thompson, K. and Smith, R., 2005. Urban Domestic Gardens (IV): The Extent of the Resource and its Associated Features. Biodiversity and Conservation, 14(14), pp.3327-3349.

(10) Kowarik, I., 2011. Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environmental Pollution, 159(8-9), pp.1974-1983.

(11) Cox, D., Shanahan, D., Hudson, H., Fuller, R. and Gaston, K., 2018. The impact of urbanisation on nature dose and the implications for human health. Landscape and Urban Planning, 179, pp.72-80.

(12) Chawla, L., 2015. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), pp.433-452.

(13) Kabisch, N., van den Bosch, M. and Lafortezza, R., 2017. The health benefits of nature-based solutions to urbanization challenges for children and the elderly – A systematic review. Environmental Research, 159, pp.362-373.

(14) Eichen, D., Matheson, B., Liang, J., Strong, D., Rhee, K. and Boutelle, K., 2018. The relationship between executive functioning and weight loss and maintenance in children and parents participating in family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 105, pp.10-16.

(15) Faber Taylor, A. and Kuo, F., 2009. Children With Attention Deficits Concentrate Better After Walk in the Park. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12(5), pp.402-409.

(16) Wu, C., McNeely, E., Cedeño-Laurent, J., Pan, W., Adamkiewicz, G., Dominici, F., Lung, S., Su, H. and Spengler, J., 2014. Linking Student Performance in Massachusetts Elementary Schools with the “Greenness” of School Surroundings Using Remote Sensing. PLoS ONE, 9(10), p.e108548.

(17) Aggio, D., Smith, L., Fisher, A. and Hamer, M., 2015. Mothers’ perceived proximity to green space is associated with TV viewing time in children: The Growing Up in Scotland study. Preventive Medicine, 70, pp.46-49.

(18) Samuelsson, K., Giusti, M., Peterson, G., Legeby, A., Brandt, S. and Barthel, S., 2018. Impact of environment on people’s everyday experiences in Stockholm. Landscape and Urban Planning, 171, pp.7-17.

(19) Collado, S., Corraliza, J., Staats, H. and Ruiz, M., 2015. Effect of frequency and mode of contact with nature on children’s self-reported ecological behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, pp.65-73.

(20) Moore, R. C. 1986. Childhood’s Domain. London, UK: Croom Helm.

(21) Liefländer, A., Fröhlich, G., Bogner, F. and Schultz, P., 2013. Promoting connectedness with nature through environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 19(3), pp.370-384.

(22) Cheng, J. and Monroe, M., 2010. Connection to Nature. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), pp.31-49.

(23) Nyari, A., Ryall, C. and Townsend Peterson, A., 2006. Global invasive potential of the house crow Corvus splendens based on ecological niche modelling. Journal of Avian Biology, 37(4), pp.306-311.

(24) Lefebvre, L., 1995. The opening of milk bottles by birds: Evidence for accelerating learning rates, but against the wave-of-advance model of cultural transmission. Behavioural Processes, 34(1), pp.43-53.

(25) Kończak, B., Cempa, M., Pierzchała, Ł. and Deska, M., 2020. Assessment of the ability of roadside vegetation to remove particulate matter from the urban air. Environmental Pollution, p.115465.

Figure 2

(a) https://www.greenroofs.com/projects/musee-du-quai-branly-greenwall/

(b) https://edinburghlivinglandscape.org.uk/project/square-metre-butterflies/

(c) https://www.greenroofs.com/projects/acros-fukuoka-prefectural-international-hall/

Figures 1 and 3 are original figures.